Capturing the Codes of Youth: Winter Vandenbrink’s Street Realities

One-on-One Interview with Winter Vandenbrink

Text: Karol Chmielewski

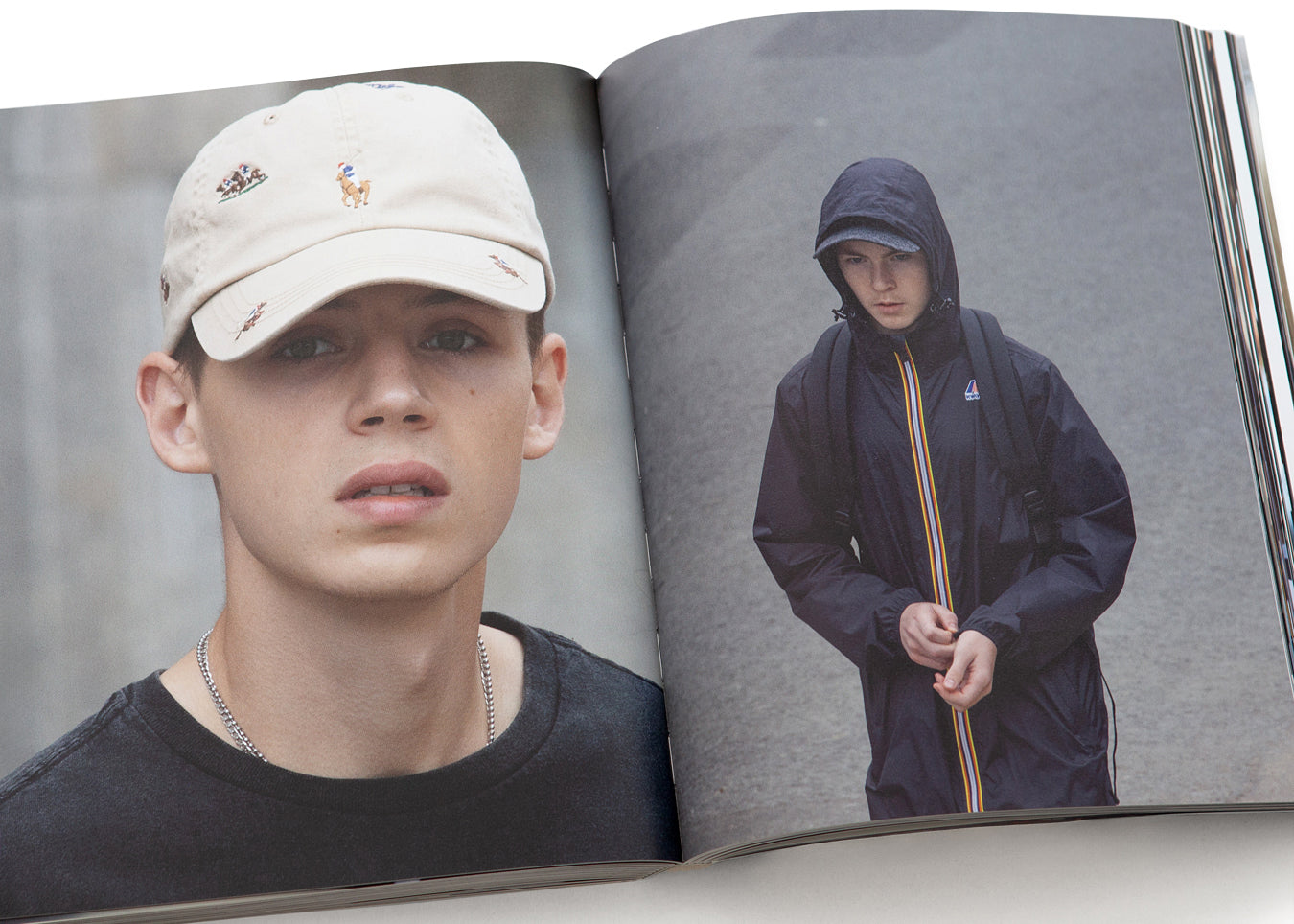

Dutch-born, Paris-based photographer Winter Vandenbrink (@wintervandenbrink) has built a reputation for his striking long-lens street photography, capturing fleeting moments of youth and style across Europe’s cities. His acclaimed book VANDALS, published by IDEA and now sold out, was hailed as one of the standout photography releases of 2024. At 10 BOOKS 10 COLORS, contributing writer Karol Chmielewski (@karchmielewski) sat down with Winter to talk about his inspirations, process, and the quiet intensity behind his images.

KC: When you’re shooting, do you ever intervene in the scene? For example, do you ask someone to turn around or repeat a gesture, or is it purely observational?

WV: No, it’s very observational. I don’t interfere. But lately, a lot of people recognize themselves on my Instagram. Sometimes I’ll ask them to do a portrait once they’re aware of it, and then I’ll direct them a bit—that’s more like a model shoot.

KC: When you shoot them, do you ever approach them afterward and say, 'Okay, I took this photo and I’m going to publish it on my Instagram'?"

WV: When I’m shooting, I’m usually far ahead—so I’d have to run after them, which would ruin my shooting day because I’d just be chasing kids! (laughs) So they usually see it on Instagram afterward.

Winter Vandenbrink - Vandals

Winter Vandenbrink - Vandals

KC: There’s often an isolating and observant quality to your work. Is that detached gaze something you consciously cultivate, as part of the atmosphere or emotional distance you’re trying to create?

WV: Yes, the observing part in my practice is very important, together with the framing and cropping of the image. I intentionally frame and crop to isolate my subjects. My pictures are already quite chaotic, with lots of layering, so I remove distractions to make the image feel more like a portrait than documentary photography. Sometimes kids genuinely stand alone on the street, absorbed in their own world—that’s real, not staged.

KC: You’ve mentioned projects like People of the Twenty-First Century and cited film directors such as Larry Clark and Apichatpong Weerasethakul as creative references. How do their cinematic sensibilities influence your photography?

WV: With Larry Clark, it’s more about the subject matter than his filmmaking style—the narratives he tells. Weerasethakul brings a mysteriousness to his films that I hope sometimes comes through in my photos. And Robert Bresson, a French director from the ’40s and ’50s, influences my sense of framing, close-ups, and atmosphere. They all come from different artistic directions, which I really enjoy.

KC: I see a lot of Larry Clark’s influence in your work. His era was different, but I think your photographs capture today’s wave of adolescence in a similar way.

WV: True. There’s also a great Spanish artist, Dario Villalba, who worked from the ’80s through the early 2000s. He photographed in a way very similar to mine—similar subjects—and he even experimented with tape, paint, and spray paint, which is really inspiring for me.

Winter Vandenbrink - Vandals

Winter Vandenbrink - Vandals

KC: You’ve cited Adorno’s Minima Moralia as an influence. Which ideas resonated with you most while creating VANDALS?

WV: Yes, this text was given to me by my boyfriend Erjan, who pointed out its relevance to today’s culture and my work. It’s mostly how Adorno describes popular culture and consumerism as the destruction of intelligence. He wrote that in 1945, but reading it now, it mirrors what you see on the streets—people en masse at events, museums, or just on the high street. I’m very interested in examining my own privileged, mainstream European society through VANDALS, rather than looking at other countries, because it’s the most relevant context for me.

KC: Did you ever consider shooting in a different city? I imagine you could uncover a whole new perspective on youth culture.

WV: Yeah, I’m hoping to go to Tokyo soon. It’s also a welfare society, so I can compare it with Europe. The youth culture there is completely different, which makes it really interesting.

KC: Looking beyond VANDALS, what directions are you exploring next?

WV: Tokyo is one. I’m also interested in filmmaking, which is quite different from photography—maybe through a collaboration with a director. I’m also working on a new book with IDEA Books, coming out around March next year, together with Linda van Deursen, who is interested in mixing in some of my fashion photography. This book will be larger, giving the photos more presence rather than focusing purely on the subject matter.

I’m also experimenting with printing, customizing, spray painting, and cutting up pictures. This is inspired by Dario Villalba, whom I told you about earlier. It’s still experimental and full of failures, but I’m enjoying the process. It might evolve into a collage or a kind of pastiche based on VANDALS.

KC: What’s your personal favorite art or photography book, and why?

WV: There are several. All of Dario Villalba’s books, many by Collier Schorr, and Chris Killip—his black-and-white photography in England is stunning, documentary-like but almost staged, a bit like Jeff Wall’s work. I also love Bruce Weber’s older books—the layouts and the whole feel are amazing. And less relatable to my own practice, but I have a big love for Derek Jarman’s films, especially the less commercial ones like The Last of England and The Angelic Conversation.

Winter Vandenbrink - Vandals (Published by IDEA, 2024)

Winter Vandenbrink - Vandals (Published by IDEA, 2024)

Contributor

Warsaw-born and London-based, Karol Chmielewski (@karchmielewski) is an artist whose multidisciplinary practice spans photography, writing, and art direction.